One theory of political change, called the “Overton window” after the political theorist who proposed it, holds that at any given time some policies are unthinkable—outside the window—until someone makes them thinkable. One way that a supposedly moderate activist group can make an unthinkable policy thinkable is to “nudge” the window forward while using the cover provided by a similarly inclined group’s more aggressive or extreme activism. Put more simply, activists play “good-cop/bad-cop”—think the dynamic between PETA and the so-called Humane Society of the United States—to force people to concede to the “good” cop. And just like a trick play in football creates confusion in the defense, this tactic confuses the issues and creates outcomes that few but the activists—both “good cops” and “bad cops”—actually want.

One theory of political change, called the “Overton window” after the political theorist who proposed it, holds that at any given time some policies are unthinkable—outside the window—until someone makes them thinkable. One way that a supposedly moderate activist group can make an unthinkable policy thinkable is to “nudge” the window forward while using the cover provided by a similarly inclined group’s more aggressive or extreme activism. Put more simply, activists play “good-cop/bad-cop”—think the dynamic between PETA and the so-called Humane Society of the United States—to force people to concede to the “good” cop. And just like a trick play in football creates confusion in the defense, this tactic confuses the issues and creates outcomes that few but the activists—both “good cops” and “bad cops”—actually want.

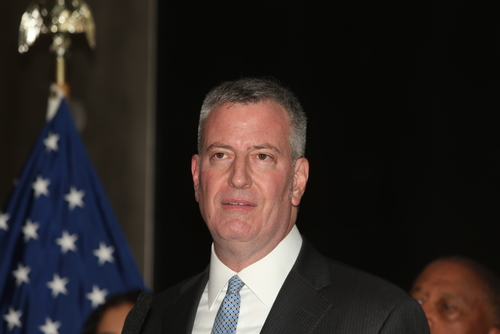

Take the sugar and soft drink scolds who are capitalizing on New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s portion-size Prohibition. One writer in the Daily Beast (and she’s not alone) tries to position the debate about which food regulations might slim down the nation as between Prohibitionism and food taxes. But there’s little to no evidence that either tactic will meaningfully impact obesity—several recent studies have found that soda taxes will cut insignificant amounts of body fat, and 71 percent of Americans predicted that Bloomberg’s latest stunt won’t trim anybody down.

The soda tax supporters are trying to capitalize on an easy mental slip. By presenting one policy as a “middle ground” between food freedom and Prohibition, activists hope that people will fall into the trap of accepting the soda tax as a false compromise. And it would be a false compromise: A Rasmussen poll last month found that only 18 percent of Americans support a sin tax on soda and other tasty treats.

Similarly, one could take the “toxic sugar” theory of Robert “No Cookies Under 18” Lustig and set it up in a false dichotomy with Twinkie tax godfather Kelly Brownell’s claims that food is addictive like cocaine. But when even Brownell concedes that “Sugar doesn’t have as strong of an effect on the brain” as actual drugs or alcohol, how meaningful can his claims of an “addiction” be? Indeed, Cambridge University researchers who conducted an examination of the evidence argued that “The vast majority of overweight individuals have not shown a convincing behavioural or neurobiological profile that resembles addiction.”

As psychiatrist warned in USA Today the first time this theory appeared: “The word ‘addiction’ is perilously close to losing any meaning.” We’d say that warning has been confirmed.

A football trick play fails when the defense doesn’t react to the distraction element. The food activist trick play will fail if consumers continue to stand up for their rights to nosh and sip without regulatory harassment.